Scrapbook 2: Aug 1962 — Vostok 3 and 4

MOSCOW, Tuesday.

THE two Russian cosmonauts were only three miles apart at one time during their space flight last week, they said in Moscow to-day at a Press conference which lasted 3¾ hours. They landed by parachute about 125 miles apart within six minutes of each other, having left their space craft in the last stages of their descent.

But in answer to a question, Lt.-Col. Popovich said that there had been no plan for linking the two ships at any time while they were in orbit, nor even for bringing them closer together by manual control.

Both Major Nikolayev and Col. Popovich were considerably franker in their answers than Major Gagarin and Major Titov had been at their first meeting with Western correspondents. While describing his landing, Major Nikolayev departed from the prepared script he had been reading.

They were sitting, with Major Gagarin and Major Titov, behind a green baize table in the assembly hall of Moscow University. Between them sat some of Russia’s space scientists.

WEIGHED 5 TONS

No room for second man

Col. Popovich said that their space craft weighed five tons each, a little bigger than the first two space ships. They could get out of their seats and walk about, but there was no room for a second space man.

Describing his landing, Major Nikolayev looked up over the heads of his audience and said: “The retro-rocket was switched on, and my capsule separated from the instrument compartment. At first the deceleration was small. Gradually it increased to 5 or 6 G.

“Then it got even more intense, and the capsule became incandescent. At first there was smoke, which became a flame, first red, then orange and then blue. This was the time of maximum pressure.

“Without my preliminary training on the centrifuge I would have had a hard time. At intervals I heard crackling sounds. At first I feared the shield was coming off the capsule, but then I realised that this was just a normal descent.

“LIKE BUMPY CART”

Pressure eased

“As the speed decreased it was like riding in a cart on a bad, bumpy road. The pressure gradually came down to 1 or 1½ G, and it was easier to endure. After a time I separated from the space ship and came down by parachute.”

Col. Popovich kept strictly to his text, but he spoke vividly without stumbling over the Russian words as Major Nikolayev had done. He said that after eating in space he had used a vacuum cleaner to clear away the crumbs.

Col. Popovich said he had been able to see Major Nikolayev’s ship, Vostok 3, during their flight in space. He had eaten fish, sausage and fried chicken.

NO DATE FOR NEXT

Programme well ahead

One point on which the space men would give nothing away was the date of the next space flight. But they said that the Russian space programme was proceeding much faster than had been expected when the first sputnik was put into orbit.

Prof. Keldysh, the president of the Academy of Sciences, who was on the rostrum with other scientists, quoted “my friend the designer of the space ships” as saying: “The time is not far distant when you will be able to go into space for the week-end.”

Prof. Keldysh agreed that Russia was also working on projects for interplanetary flight. But before a man was sent to another planet there would have to be many previous automatic space probes.

U.S. ACCUSED

“Space made ‘dirty’”

He accused the United States of making space “dirty” with its high-altitude atomic tests. “This meant that we could not send up spacemen in a higher orbit than Gagarin and Titov,” he said.

An American correspondent asked whether space ships Vostok 3 and 4 could carry nuclear weapons and photograph military objectives. Major Popovich said: “Our ships are used, and will be used, for peaceful purposes only.”

When a Western correspondent asked when they would be allowed to see a space launching, Prof. Keldysh replied: “We’ll use these rockets for peaceful purposes.

“But while people call for war we must guard our most powerful missiles. If Western governments sign a treaty of general disarmament Western correspondents will be able to see a launching.”

KENNEDY STATEMENT

From Our Own Correspondent WASHINGTON, Wednesday.

President Kennedy said to-day the United States was well behind Russia in space exploration. “But I believe that by the end of the decade the United States will be ahead.”

The President was asked at his Press conference how he sized up America’s space programme in the light of the Russian “Space Twin’s” feat. He said America was well behind Russia. Anyone who said otherwise was misleading the American people, but America would lead before 1970.

The lesson of Vostoks 3 and 4 is reliability and precision—reliability of launch vehicles and precision of guidance into orbit.

Whether or not an attempt is made to connect the two craft while in orbit—and the wording of the official announcement implied that this was not a primary aim—the routine way in which two manned space craft have been launched into similar, prolonged orbits around the earth within 24 hours surpasses any previous achievement in the field of earth orbital flight.

The series of seven unmanned Cosmos satellites which were launched between March 16 and July 28 this year did not appear to mark a major advance, although as their weight was not disclosed and few details of the craft were given, it was impossible to know just how advanced they were. But one of their stated purposes was to study “the energy composition of the earth’s radiation belts with the aim of evaluating the radiation danger of long cosmic flights.”

A starting point

Speculation on the type of “long cosmic flight” envisaged certainly included extended earth orbital flights by two men—but it was assumed that the two cosmonauts would share the same spacecraft. Once again, Soviet space technology has pulled a spectacular rabbit out of the hat, in the true tradition of the series of impressive achievements from Sputnik I in October, 1957, to Major Titov’s day in orbit just one year ago.

The technique of connecting together two or more spacecraft sections while in orbit around the earth is bound to become one of the routine tricks of space flight within the next few years, and may well be used as a starting point for manned trips to the moon. To get to the moon and back using only one launch vehicle would require a gigantic rocket; in spite of which, the payload carried would be small. Smaller rockets and larger payloads are made possible by the rendezvous technique.

If the Russians are in fact planning to use this technique for manned flight to the moon, this will be in marked contrast to the way the United States is planning to get there. The US National Aeronautics and Space Administration spent 12 months studying the problem and only last month announced its decision not to employ earth orbital rendezvous in its project Apollo programme of manned lunar exploration.

The American intention is to place a three-man spacecraft in orbit around the moon in one direct shot from earth using an advanced Saturn booster. While in orbit around the moon a small two-man “lunar excursion module” will detach itself from the main body of the craft and will descend to the lunar surface.

After the two astronauts have completed their work on the moon, their excursion vehicle will take off, leaving its tripod legs behind it, and connect up again with the parent spacecraft, which will still be circling the moon. The astronauts will transfer to the main craft, the excursion vehicle will be jettisoned, and the return journey to earth will begin. In effect, lunar orbital rendezvous has been substituted for earth orbital rendezvous in the US plan.

In announcing this hazardous-sounding operation last month, the National Aeronautic and Space Administration said that this method was believed to provide a higher probability of success with “essentially equal” safety. Also, it promised success “some months earlier” than other methods, and would be 10 to 15 per cent cheaper.

Soviet thinking may well be running along similar lines, for experiments in earth orbital rendezvous will be necessary whichever technique is finally employed for the lunar flight. The same methods of orbit adjustment and spacecraft control for rendezvous will be needed whether the body beneath happens to be the earth or the moon.

The US Gemini programme of earth orbital flight by two-man versions of the existing Mercury craft, due to begin next year, will include exercises in orbital rendezvous. In this programme, however, the initial tests will involve a manned Gemini craft connecting in orbit with an unmanned piece of metal—an Agena upper-stage rocket body.

US experiment

Although little has been said about it, the Americans have already tried to achieve earth orbital rendezvous of a kind. This attempt, part of a military “satellite inspector” programme known by the code name Saint, was made in April. An Atlas-Agena and a Blue Scout were launched from different bases at different times with the object of a rendezvous in orbit between their two payloads, but the experiment was unsuccessful following the second-stage failure of one of the rockets.

The agonising postponements, from day to day and week to week, of many launchings of American spacecraft from Cape Canaveral underlines the immense achievement of the Soviet Union over the weekend. Two men in orbit, circling the earth in separate vehicles and talking to each other—space is beginning to become crowded.

The fact that the orbits into which Vostoks 3 and 4 were placed are almost identical indicates a standard of accuracy which has never before been achieved, even by the Russians. The US Discoverer satellite programme, begun in 1959 and still continuing, has not approached this standard, even with a time between identical launchings of weeks rather than one day. Neither has the Soviet Cosmos series which preceded Vostoks 3 and 4.

The best and most recent US example of orbital precision occurred on August 5, when a secret Air Force launching of Atlas-Agena from Point Arguello, California, achieved for the first time by any country, an almost exactly circular orbit.

The US lunar exploration programme, Apollo, is already being tackled at what many observers believe to be too fast a pace, because of the prestige importance which President Kennedy attaches to it. The effect of this weekend’s launchings, and their implications for the future, will clearly be to increase the pressure still further.

MR. KHRUSCHEV said yesterday in his Red Square welcome to the spacemen that there is no mystery about their flights. This is not strictly true.

On this occasion there are no doubts that the flights actually took place. But the Russians have not been wildly forthcoming over the facts about the flights.

Was a rendezvous intended? Did the men manipulate their craft towards each other? How far apart were they when they saw each other? Was there anything that did not go as planned?

These are all crucial questions. Subsidiary questions concern the size, weight and furnishings of the space ships. How was the biological environment controlled? Did weightlessness for such a long period have no ill effects at all?

In his speech yesterday Mr. Khruschev reasserted that the spacemen had been able to see each other. Now, even large ships become small in the enormity of space. And you would have to be fairly close to a bus to see it.

10 Years ahead

Despite the meagre facts given to us, Sir Bernard Lovell, director of the radio astronomy station at Jodrell Bank, has summed up the situation. He says the Russians are 10 years ahead of the Americans.

Many Americans will not go so far. Ex-President Eisenhower said last week he thought the Americans were still on top.

Yet there is one fact that has been blatantly true ever since Sputnik I was fired into orbit nearly five years ago. This is that the sort of rockets the Russian space scientists have been able to call upon from the military armoury have been colossal.

Pictures not revealing

They were big even at the start of the race. Russia has never sent up anything weighing less than 180lb. and practically everything sent up has been over one ton. The Americans have fired objects even as small as 3½lb. into orbit. Their Mercury capsule soon to be launched for six orbits weighs just on one ton.

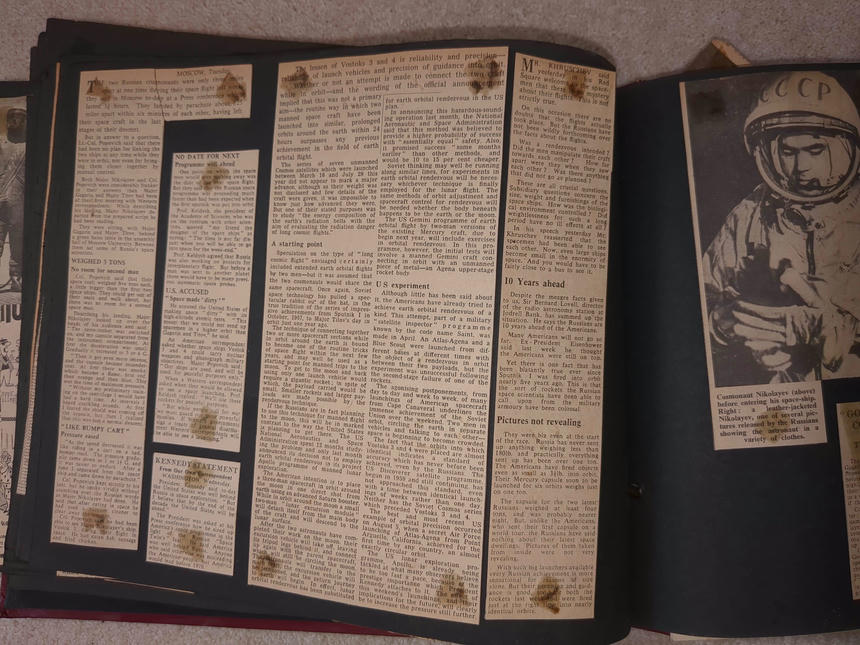

The capsule for the two latest Russians weighed at least four tons, and was probably nearer eight. But, unlike the Americans, who sent their first capsule on a world tour, the Russians have said nothing about their latest space dwellings. Pictures of them taken from inside were not very revealing.

With such big launchers available every Russian achievement is more sensational for reasons of size alone. But their precision and guidance is good, too, for both the rockets last week-end were fired just at the right time into nearly identical orbits.