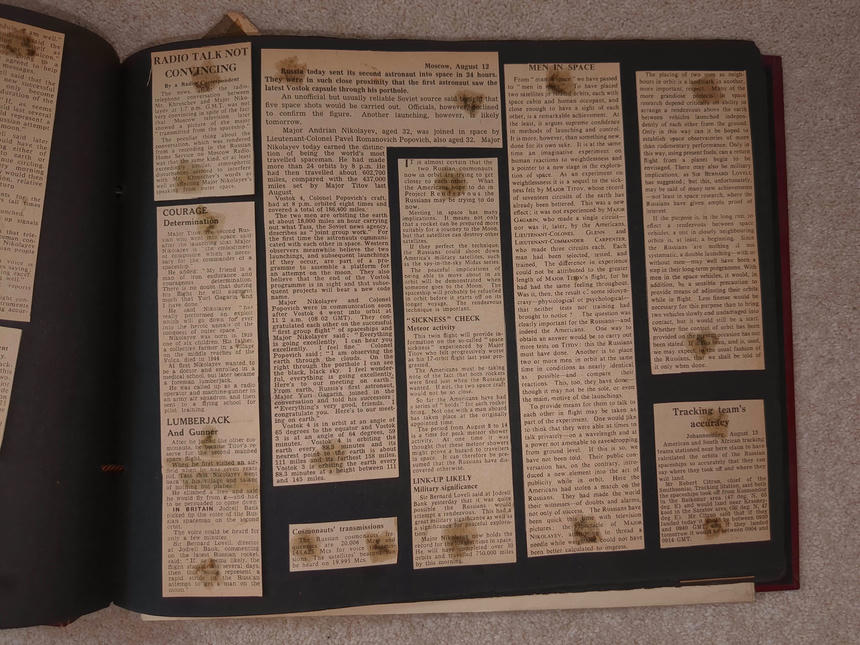

Scrapbook 2: Aug 1962 — Vostok 3 and 4

RADIO TALK NOT CONVINCING

By a Radio Correspondent

The news, about the radio-telephone conversation between Mr. Khruschev and Major Nikolayev at 1.7 p.m. G.M.T. was not very convincing in spite of the fact that Moscow television later showed a picture of the major “transmitted from the spaceship.”

The peculiar thing about the conversation, which was rendered from a recording in the Russian Home Service on Moscow Radio, was that the same kind, or at least exceedingly similar, atmospheric disturbances seemed to interfere with Mr. Khruschev’s words as well as affecting Major Nikolayev’s speaking from outer space.

COURAGE

Determination

Major Titov, the second Russian who went into space, said after the launching that Major Nikolayev is “the embodiment of composure, which is necessary for the commander of a spaceship.”

He added: “My friend is a man of iron endurance and courageous determination. There is no doubt that during his flight he will augment much that Yuri Gagarin and I have done.”

He said Nikolayev “has really performed an exploit which will go down for ever into the heroic annals of the conquest of outer space.”

Nikolayev was born in 1929, one of six children. His father, a collective farmer in a village on the middle reaches of the Volga, died in 1944.

At first Nikolayev wanted to be a doctor and enrolled in a medical school, but later became a foreman lumberjack.

He was called up as a radio operator and machine-gunner in an army air squadron, and then sent to a flying school for pilot training.

LUMBERJACK

And Gunner

After he joined the other cosmonauts, he became Titov’s reserve for the second manned space flight.

When he first visited an airfield when he was seven years old, Tass said, Nikolayev went back to his village and talked of nothing but planes.

He climbed a tree and said he would fly from it—had to be persuaded to come down.

IN BRITAIN Jodrell Bank picked up the voice of the Russian spaceman on the second orbit.

The voice could be heard for only a few minutes.

Sir Bernard Lovell, director at Jodrell Bank, commenting on the latest Russian rocket, said: “If, as seems likely, the flight should last several days, then this would represent a rapid stride in the Russian attempt to get a man on the moon.”

Moscow, August 12

Russia today sent its second astronaut into space in 24 hours. They were in such close proximity that the first astronaut saw the latest Vostok capsule through his porthole.

An unofficial but usually reliable Soviet source said tonight that five space shots would be carried out. Officials, however, declined to confirm the figure. Another launching, however, is likely tomorrow.

Major Andrian Nikolayev, aged 32, was joined in space by Lieutenant-Colonel Pavel Romanovich Popovich, also aged 32. Major Nikolayev today earned the distinction of being the world’s most travelled spaceman. He had made more than 24 orbits by 8 p.m. He had then travelled about 602,700 miles, compared with the 437,000 miles set by Major Titov last August.

Vostok 4, Colonel Popovich’s craft, had at 8 p.m. orbited eight times and covered a total of 186,400 miles.

The two men are orbiting the earth at about 18,000 miles an hour carrying out what Tass, the Soviet news agency, describes as “joint group work.” For the first time the astronauts communicated with each other in space. Western observers meanwhile believe the two launchings, and subsequent launchings if they occur, are part of a programme to assemble a platform for an attempt on the moon. They also believe that the end of the Vostok programme is in sight and that subsequent projects will bear a new code name.

Major Nikolayev and Colonel Popovich were in communication soon after Vostok 4 went into orbit at 11 2 a.m. (08 02 GMT). They congratulated each other on the successful “first group flight” of spaceships and Major Nikolayev said: “Everything is going excellently. I can hear you excellently. I feel fine.” Colonel Popovich said: “I am observing the earth through the clouds. On the right through the porthole I can see the black, black sky. I feel wonderful, everything is going excellently. Here’s to our meeting on earth.” From earth, Russia’s first astronaut, Major Yuri Gagarin, joined in the conversation and told his successors: “Everything’s very good, friends. I congratulate you. Here’s to our meeting on earth.”

Vostok 4 is in orbit at an angle of 65 degrees to the equator and Vostok 3 is at an angle of 64 degrees, 59 minutes. Vostok 4 is orbiting the earth every 88.5 minutes and its nearest point to the earth is about 111 miles and its farthest 158 miles. Vostok 3 is orbiting the earth every 88.3 minutes at a height between 111 and 145 miles.

Cosmonauts’ transmissions

The Russian cosmonauts’ frequencies are 20.006 Mcs and 143.625 Mcs for voice transmissions. The satellites’ beacons can be heard on 19.995 Mcs.

IT is almost certain that the two Russian cosmonauts now in orbit are trying to get closer to each other. What the Americans hope to do in Project Rendezvous the Russians may be trying to do now.

Meeting in space has many implications. It means not only that a rocket can be prepared more suitably for a journey to the Moon, but that satellites can destroy other satellites.

If they perfect the technique, the Russians could shoot down America’s military satellites, such as the spy-in-the-sky Midas series.

The peaceful implications of being able to move about in an orbit will be demonstrated when someone goes to the Moon. The spaceship will probably be refuelled in orbit before it starts off on its longer voyage. The rendezvous technique is important.

“SICKNESS” CHECK

Meteor activity

This twin flight will provide information on the so-called “space sickness” experienced by Major Titov who felt progressively worse as his 17-orbit flight last year progressed.

The Americans must be taking note of the fact that both rockets were fired just when the Russians wanted. If not, the two space craft would not be so close.

So far the Americans have had a series of “holds” for each rocket firing. Not one with a man aboard has taken place at the originally appointed time.

The period from August 8 to 14 is a time for peak meteor shower activity. At one time it was thought that these meteor showers might prove a hazard to travellers in space. It can therefore be presumed that the Russians have discovered otherwise.

LINK-UP LIKELY

Military significance

Sir Bernard Lovell said at Jodrell Bank yesterday that it was quite possible the Russians would attempt a rendezvous. This had a great military significance as well as a significance for peaceful exploration.

Major Nikolayev now holds the record for the longest time in space. He will have completed over 30 orbits and travelled 750,000 miles by this morning.

MEN IN SPACE

From “man in space” we have passed to “men in space”. To have placed two satellites in related orbits, each with space cabin and human occupant, and close enough to have a sight of each other, is a remarkable achievement. At the least, it argues supreme confidence in methods of launching and control. It is more, however, than something new, done for its own sake. It is at the same time an imaginative experiment on human reactions to weightlessness and a pointer to a new stage in the exploration of space. As an experiment on weightlessness it is a sequel to the sickness felt by MAJOR TITOV, whose record of seventeen circuits of the earth has already been bettered. This was a new effect; it was not experienced by MAJOR GAGARIN, who made a single circuit—nor was it, later, by the Americans, LIEUTENANT-COLONEL GLENN and LIEUTENANT-COMMANDER CARPENTER, who made three circuits each. Each man had been selected, tested, and trained. The difference in experience could not be attributed to the greater length of MAJOR TITOV’s flight, for he had had the same feeling throughout. Was it, then, the result of some idiosyncrasy—physiological or psychological—that neither tests nor training had brought to notice? The question was clearly important for the Russians—and indeed the Americans. One way to obtain an answer would be to carry out more tests on TITOV: this the Russians must have done. Another is to place two or more men in orbit at the same time in conditions as nearly identical as possible—and compare their reactions. This, too, they have done—though it may not be the sole, or even the main, motive of the launchings.

To provide means for them to talk to each other in flight may be taken as part of the experiment. One would like to think that they were able at times to talk privately—on a wavelength and at a power not amenable to eavesdropping from ground level. If this is so, we have not been told. Their public conversation has, on the contrary, introduced a new element into the art of publicity while in orbit. Here the Americans had stolen a march on the Russians. They had made the world their witnesses—of doubts and alarms, not only of success. The Russians have been quick this time with television pictures; the spectacle of MAJOR NIKOLAYEV, attempting to thread a needle while weightless, could not have been better calculated to impress.

The placing of two men as neighbours in orbit is a landmark in another, more important, respect. Many of the more grandiose projects in space research depend critically on ability to arrange a rendezvous above the earth between vehicles launched independently of each other from the ground. Only in this way can it be hoped to establish space observatories of more than rudimentary performance. Only in this way, using present fuels, can a return flight from a planet begin to be envisaged. There may also be military implications, as SIR BERNARD LOVELL has suggested; but this, unfortunately, may be said of many new achievements—not least in space research, where the Russians have given ample proof of interest.

If the purpose is, in the long run, to effect a rendezvous between space vehicles, a test in closely neighbouring orbits is, at least, a beginning. Since the Russians are nothing if not systematic, a double launching—with or without men—may well have been a step in their long-term programme. With men in the space vehicles, it would, in addition, be a sensible precaution to provide means of adjusting their orbits while in flight. Less finesse would be necessary for this purpose than to bring two vehicles slowly and undamaged into contact, but it would still be a start. Whether fine control of orbit has been provided on the present occasion has not been stated. If it has been, and is, used, we may expect, in the usual fashion of the Russians, that we shall be told of it only when done.

Tracking team’s accuracy

Johannesburg, August 13

American and South African tracking teams stationed near here claim to have calculated the orbits of the Russian spaceships so accurately that they can say where they took off and where they will land.

Mr Robert Citron, chief of the Smithsonian Tracking Station, said both the spaceships took off from Kosmondor in the Baikonur area (47 deg. N, 65 deg. E) and would land near Krasneykoot in the Saratov area (50 deg. N, 47 deg E). Mr Citron said that if they landed today it would be between 0930 and 0940 GMT, and if they landed tomorrow it would be between 0904 and 0914 GMT.