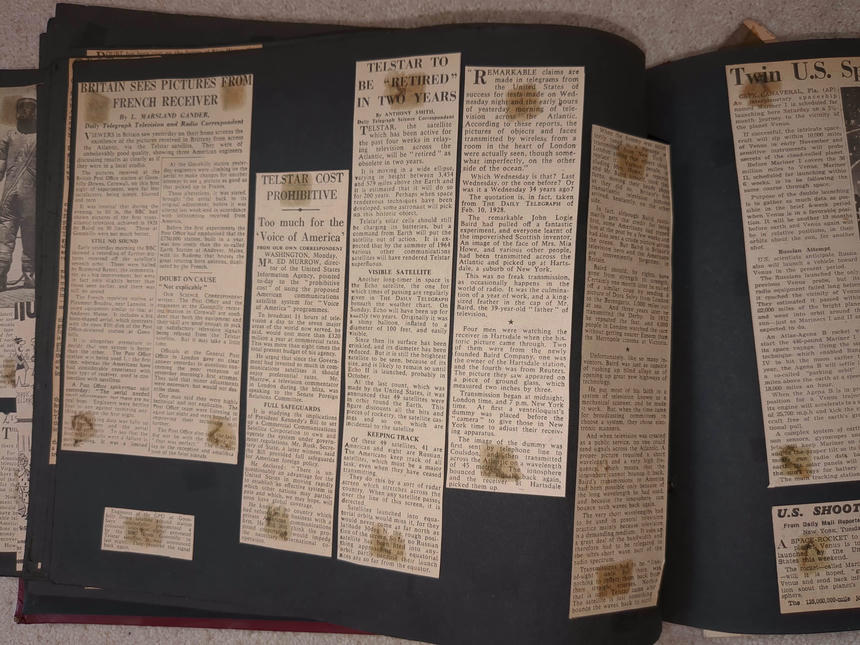

Scrapbook 2: Jul–Aug 1962 — Telstar

BRITAIN SEES PICTURES FROM FRENCH RECEIVER

By L. MARSLAND GANDER, Daily Telegraph Television and Radio Correspondent

VIEWERS in Britain saw yesterday on their home screens the excellence of the pictures received in Brittany from across the Atlantic, via the Telstar satellite. They were of unbelievably good quality, showing three American engineers discussing results as clearly as if they were in a local studio.

The pictures received at the British Post Office station at Goonhilly Downs, Cornwall, on this first night of experiment, were far less satisfactory, being jumpy, blurred and torn.

It was ironical that during the evening, to fill in, the BBC had shown pictures of the first transatlantic television, achieved in 1928 by Baird on 30 lines. Those at Goonhilly were not much better.

STILL NO SOUND

Early yesterday morning the BBC showed a recording of further pictures received off the satellite’s seventh orbit. These were hailed by Raymond Baxter, the commentator, as a big improvement, but were in fact only slightly better than those seen earlier, and there was still no sound.

The French receiving station at Pleumeur Boudou, near Lannion, is using equipment similar to that at Andover, Maine. It includes a big horn-shaped aerial, which contrasts with the open 85ft dish of the Post Office-designed station at Goonhilly.

It is altogether premature to decide that one system is better than the other. The Post Office station was being used for the first time, whereas the Americans have had considerable experience with their type of receiver, used in conjunction with satellites.

A Post Office spokesman said yesterday: “The aerial needed small adjustments but there are no real bugs. Engineers were betting four to one against receiving anything at all on the first night.

“The tracking data was fully up to expectations and the aerial tracked perfectly. To say that the first night results were a failure is quite wrong. It was a limited success.”

At the Goonhilly station yesterday engineers were climbing on the aerial to make changes for another attempt to see a picture as good as that picked up in France.

These alterations, it was stated, brought the aerial back to its original adjustment, before it was altered last week-end in accordance with inforamtion received from America.

Before the first experiments the Post Office had emphasised that the £750,000 station, built in a year, was less costly than the so-called Earth Station at Andover, Maine, with its Radome that houses the great rotating horn antenna, duplicated by the French.

DOUBT ON CAUSE

“Not explicable”

OUR SCIENCE CORRESPONDENT writes: The Post Office and the engineers at the Goonhilly receiving station in Cornwall are confident that both the equipment and their skill are good enough to pick up satisfactory television signals being relayed from the Telstar satellite. But it may take a little time.

Officials at the General Post Office in London gave no clear answer yesterday to questions concerning the poor reception of yesterday morning’s first attempt. They said that minor adjustments were necessary, but would not describe them.

One man said they were highly technical and not explicable. The Post Office team were listening in again last night and were hopeful of improving their technique still further.

The Post Office also said the fault did not lie with the tracking for “that was perfect.” The difficulty lay in the reception and amplification of the faint signals.

Engineers of the GPO at Goonhilly Down satellite ground station have successfully transmitted a coloured television signal generated by the BBC from Goonhilly to Telstar satellite, it was announced last night. They received the signal back again.

TELSTAR COST PROHIBITIVE

Too much for the ‘Voice of America’

FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT WASHINGTON, Monday.

MR. ED MURROW, director of the United States Information Agency, pointed to-day to the “prohibitive cost” of using the proposed American communications satellite system for “Voice of America” programmes.

To broadcast 1½ hours of television a day to the seven major areas of the world now served, he said, would cost more than £320 million a year at commercial rates. This was more than eight times the total present budget of his agency.

He urged that since the Government had invested so much in communications satellites it should enjoy preferential rates. Mr. Murrow, a television commentator in London during the blitz, was speaking to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

FULL SAFEGUARDS

It is studying the implications of President Kennedy’s Bill to set up a Commercial Communications Satellite Corporation to own and operate the system under government regulations. Mr. Rusk, Secretary of State, a later witness, said the Bill provided full safeguards for American foreign policy.

He declared: “There is unquestionably an advantage for the United States in moving rapidly to establish an effective system in which other nations may participate and which, we may hope, will soon have global coverage.

He knew of no country which had refused to do business with a private American communications firm. He did not think the proposed corporation would impede the necessary international cooperation.

TELSTAR TO BE “RETIRED” IN TWO YEARS

By ANTHONY SMITH, Daily Telegraph Science Correspondent

TELSTAR, the satellite which has been active for the past four weeks in relaying television across the Atlantic, will be “retired” as obsolete in two years.

It is moving in a wide ellipse, varying in height between 3,454 and 579 miles above the Earth and it is estimated that it will do so for 200 years. Perhaps when space rendezvous techniques have been developed, some astronaut will pick up this historic object.

Telstar’s solar cells should still be charging its batteries, but a command from Earth will put the satellite out of action. It is expected that by the summer of 1964 various other communications satellites will have rendered Telstar superfluous.

VISIBLE SATELLITE

Another long-timer in space is the Echo satellite, the one for which times of passing are regularly given in THE DAILY TELEGRAPH beneath the weather chart. On Sunday, Echo will have been up for exactly two years. Originally it was a shiny balloon, inflated to a diameter of 100 feet, and easily visible.

Since then its surface has been crinkled, and its diameter has been reduced. But it is still the brightest satellite to be seen, because of its size, and is likely to remain so until Echo II is launched, probably in October.

At the last count, which was made by the United States, it was announced that 49 satellites were in orbit round the Earth. This figure discounts all the bits and pieces of rocketry, the satellite casings and so on, which are incidental to the satellite.

KEEPING TRACK

Of these 49 satellites, 41 are American and eight are Russian. The Americans keep track of all satellites, which must be a major task, even when they have ceased transmitting.

They do this by a sort of radar screen which stretches across the country. When any satellite passes over the line of this screen, it is detected.

Satellites launched into equatorial orbits would miss it, for they would never come as far north as latitude 30deg N, the rough position of the screen. So far no Russian satellite has been fired into anything approaching an equatorial orbit, partly because their launch sites are so far from the equator.

“REMARKABLE claims are made in telegrams from the United States of success for tests made on Wednesday night and the early hours of yesterday morning of television across the Atlantic. According to these reports, the pictures of objects and faces transmitted by wireless from a room in the heart of London were actually seen, though somewhat imperfectly, on the other side of the ocean.”

Which Wednesday is that? Last Wednesday, or the one before? Or was it a Wednesday 34 years ago?

The quotation is, in fact, taken from THE DAILY TELEGRAPH of Feb. 10, 1928.

The remarkable John Logie Baird had pulled off a fantastic experiment, and everyone learnt of the impoverished Scottish inventor. An image of the face of Mrs. Mia Howe, and various other people, had been transmitted across the Atlantic and picked up at Hartsdale, a suburb of New York.

This was no freak transmission, as occasionally happens in the world of radio. It was the culmination of a year of work, and a king-sized feather in the cap of Mr. Baird, the 39-year-old “father” of television.

Four men were watching the receiver in Hartsdale when the historic picture came through. Two of them were from the newly founded Baird Company, one was the owner of the Hartsdale station, and the fourth was from Reuters. The picture they saw appeared on a piece of ground glass, which measured two inches by three.

Transmission began at midnight, London time, and 7 p.m. New York time. At first a ventriloquist’s dummy was placed before the “camera” to give those in New York time to adjust their receiving apparatus.

The image of the dummy was first sent by telephone line to Coulsdon, and then transmitted across the Atlantic on a wavelength of 45 metres. The ionosphere bounced the signals back again, and the receiver at Hartsdale picked them up.

When the dummy was satisfactorily tuned in, a message was transmitted from New York to London asking that others should replace it. Various people, including Mrs. Howe, a reporter, and Mr. Baird himself, took their turns, moving their heads about as they did so. Britain’s first transatlantic television pictures arrived, hesitantly, on the other side.

In fact, although Baird customarily gets the credit for being first, some Americans had pipped him at the post by a few weeks and had also sent a crude picture across the ocean. But Baird is Britain’s television hero and the Americans are conveniently forgotten in Britain.

Baird should, by rights, have gone from strength to strength. Certainly one month later he pulled off a similar coup by sending a picture of Dora Selvy from London to the Berengaria, 1,000 miles out at sea. And three years later he transmitted the Derby. In 1932 he repeated the feat, and 4,000 people in London watched the race without getting nearer Epsom than the Metropole cinema at Victoria.

Unfortunately, like so many inventors, Baird was just as capable of rushing up blind alleys as of opening up great new highways of technology.

He put most of his faith in a system of television known as a mechanical scanner, and he made it work. But, when the time came for broadcasting committees to choose a system, they chose electronic scanners.

And when television was created as a public service, no one could send signals across the Atlantic. A proper picture required a short wavelength and a very high frequency, which means that the ionosphere cannot bounce it back. Baird’s transmissions to America had been possible only because of the long wavelength he had used, and because the ionosphere can bounce such waves back again.

The very short wavelengths had to be used in general television practice mainly because television is a demanding medium. It uses up a great deal of the bandwidth and therefore had to be relegated to the ultra-short wave part of the radio spectrum.

Transmissions had to be “line-of-sight” only, for there was nothing to reflect them back from their straight courses. Nothing, that is until Telstar came along. The satellite is just something to bounce the waves back to earth.