Scrapbook 2: Jul 1962 — Telstar

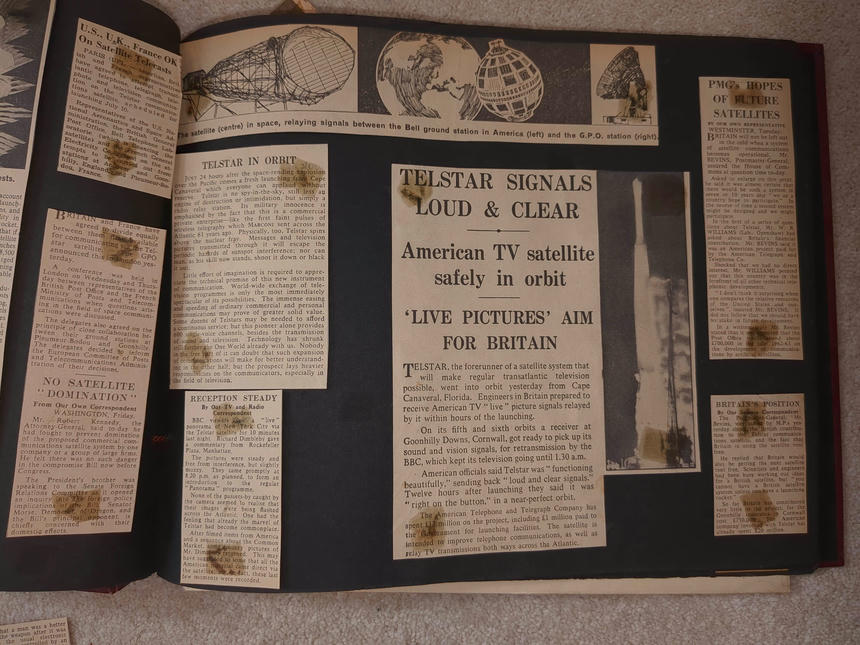

The satellite (centre) in space, relaying signals between the Bell ground station in America (left) and the G.P.O. station (right).

TELSTAR IN ORBIT

JUST 24 hours after the space-rending explosion over the Pacific comes a fresh launching from Cape Canaveral which everyone can applaud without reserve. Telstar is no spy-in-the-sky, still less an engine of destruction or intimidation, but simply a radio relay station. Its military innocence is emphasised by the fact that this is a commercial private enterprise—like the first faint pulses of wireless telegraphy which MARCONI sent across the Atlantic 61 years ago. Physically, too, Telstar spins above the nuclear fray. Messages and television pictures transmitted through it will escape the periodic hazards of sunspot interference; nor can man, as his skill now stands, shoot it down or black it out.

Little effort of imagination is required to appreciate the technical promise of this new instrument of communication. World-wide exchange of television programmes is only the most immediately spectacular of its possibilities. The immense easing and speeding of ordinary commercial and personal communications may prove of greater solid value. Some dozens of Telstars may be needed to afford a continuous service; but this pioneer alone provides 600 single-voice channels, besides the transmission of sound and television. Technology has shrunk still further the One World already with us. Nobody in the free part of it can doubt that such expansion of communications will make for better understanding in the other half; but the prospect lays heavier responsibilities on the communicators, especially in the field of television.

RECEPTION STEADY

By Our TV and Radio Correspondent

BBC viewers saw a “live” panorama of New York City via the Telstar satellite for 10 minutes last night. Richard Dimbleby gave a commentary from Rockefeller Plaza, Manhattan.

The pictures were steady and free from interference, but slightly muzzy. They came promptly at 8.20 p.m. as planned, to form an introduction to the regular “Panorama” programme.

None of the passers-by caught by the camera seemed to realise that their images were being flashed across the Atlantic. One had the feeling that already the marvel of Telstar had become commonplace.

After filmed items from America and a sequence about the Common Market, some muzzy pictures of Mr. Dimbleby returned. This may have suggested to some that all the American material came direct via the satellite; but, in fact, these last few moments were recorded.

TELSTAR SIGNALS LOUD & CLEAR

American TV satellite safely in orbit

‘LIVE PICTURES’ AIM FOR BRITAIN

TELSTAR, the forerunner of a satellite system that will make regular transatlantic television possible, went into orbit yesterday from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Engineers in Britain prepared to receive American TV “live” picture signals relayed by it within hours of the launching.

On its fifth and sixth orbits a receiver at Goonhilly Downs, Cornwall, got ready to pick up its sound and vision signals, for retransmission by the BBC, which kept its television going until 1.30 a.m.

American officials said Telstar was “functioning beautifully,” sending back “loud and clear signals.” Twelve hours after launching they said it was “right on the button,” in a near-perfect orbit.

The American Telephone and Telegraph Company has spent £17 million on the project, including £1 million paid to the Government for launching facilities. The satellite is intended to improve telephone communications, as well as relay TV transmissions both ways across the Atlantic.

PMG’s HOPES OF FUTURE SATELLITES

BY OUR OWN REPRESENTATIVE WESTMINSTER, Tuesday.

BRITAIN will not be left out in the cold when a system of satellite communications becomes operational, Mr. BEVINS, Postmaster-General, assured the House of Commons at question time to-day.

Asked to enlarge on this point, he said it was almost certain that there would be such a system in seven or 10 years and “we as a country hope to participate.” In the course of time a second system might be designed and we might participate.

In the first of a series of questions about Telstar, Mr. W. R. WILLIAMS (Lab., Openshaw) had asked about Britain’s financial contribution. Mr. BEVINS said it was an American project paid for by the American Telegraph and Telephone Co.

Shocked that we had no direct interest, Mr. WILLIAMS pointed out that this country was in the forefront of all other technical telephonic developments.

“I don’t think it surprising when one compares the relative resources of the United States and ourselves”, insisted Mr. BEVINS. It did not follow that we should have no stake in future development.

In a written reply Mr. Bevins stated that it was expected that the Post Office would spend about £700,000 in the year 1962-63 on the development of communications by artificial satellites.

BRITAIN’S POSITION

By Our Science Correspondent

The Postmaster-General, Mr. Bevins, was asked by M.P.s yesterday about the British contribution to the Telstar communications satellite, and the fact that Britain is using the satellite rent free.

He replied that Britain would also be getting the next satellite rent free. Scientists and engineers had been busy working out ideas for a British satellite, but “you cannot have a British satellite system unless you have a launching rocket.”

So far Britain has contributed very little to the project, for the Goonhilly apparatus in Cornwall cost £750,000. The American company involved with Telstar has already spent £20 million.