Scrapbook 1: 1962? — John Wyndham

NOTE: The writer must be John Wyndham (author of The Day of the Triffids), writing here about alien life and transhumanism.

THERE seems to have been some confusion about Space lately. The fellow who gets himself shot a little way off the Earth and goes round it a few times is a brave man, but he is not a Spaceman.

He is certainly a pioneer. It is because of him that there will be men on the Moon, probably on Mars, and very likely on Venus, too, and that there may be manned satellites in orbit about the Earth.

But a little bit of our own solar backyard is not Space.

Space is a very big place. Journeys to even the nearest stars would take thousands of years by rocket ships as we know them.

Probably the rocket ship’s greatest contribution will be to make possible an observatory on the Moon where the further study of Space will be unhampered by an atmosphere.

What shall we be looking for in Space?

Sir Bernard Lovell, and others, have pointed out that some of the planets in Space are probably very like Earth.

Many of them may therefore have produced lifeforms much like ours, and on numbers of these planets evolution may parallel that on Earth.

SHOCK

THERE is a disconcerting implication in this business, for if, as Sir Bernard maintains, there are great numbers of planets very similar to our own, then there must be millions that are not quite similar to our own.

And, among them, planets where things that are merely unlikely possibilities here have actually taken place.

You see where this leads? It means that on various planets all those possible-improbabilities that I thought I had imagined in my books—the triffids, the deep-sea monsters, the dangerous children, the woman’s world, and the rest of them may really exist.

It comes as a great shock to a writer of fiction, particularly of my kind of fiction, to learn on such authority that he may have been mistakenly writing facts all the time.

I am sometimes asked: “Why do you write such far-fetched stories?”

But, of late, I do seem to meet the question less frequently, and find myself wondering whether it is simply going out of fashion, or whether in a world that is growing more “far-fetched” every day it is just losing its meaning.

It seems to me that, in a world that has changed, and is changing, so fast, curiosity about some of the things that might conceivably happen is perfectly natural.

Moreover, the signs are that we are drawing close to the opening of a new phase; one that is going to affect us more more intimately than all the scientific discoveries of the past.

The spectacular progress of the last century and a half was conducted almost entirely by engineers to begin with, and then by chemists and physicists.

They have given us a better standard of living, less drudgery, more interests.

Yet progress has had little effect upon us, ourselves.

But coming to the fore now are the newer scientists, the biologists, the geneticists, the psychologists, the sociologists, the pathologists, and the rest with new knowledge leading to discoveries which are going to change not simply the way we live, but us.

When I wrote “The Midwich Cuckoos” (filmed as “The Village of the Damned”) a few years ago, I centred it round a group of children who could read one another’s thoughts and combine them to make a very powerful mind.

It seemed fanciful then but in even a short time it has begun to seem less so.

Only a few days ago came the announcement that the great Westinghouse Corporation in America is conducting research into direct mental communication.

Important companies do not start such projects without some good reason to expect results.

Recently announced was a breakthrough in genetics called DNA, which appears to be the first step that may lead to the control of heredity.

ANGELS

IT could perhaps lead on to the day when your granddaughter hands in her recipe for her baby:

“A boy, please. I’d like him to have his father’s nose, my colour eyes, his father’s brains, but with more of my practical sense. A bit more of my drive added to his father’s patience. . . .”

And so on, so that the chances of Mummy’s little angel actually being angelic would be greatly improved.

On the other hand, there are a lot of people uninterested in angels. A forceful, ambitious couple might well wish their offspring to have the combined drive of both, and the softer qualities left out.

He would probably get along pretty well, but how much damage would he do to others on his way?

So, as the results of this discovery develop, there will loom behind them a huge two-part question: Are we going to endow children with ambition, or with the human virtues?

There will be more straightforward, but still important, questions, too: How, for instance, if the parents are to have any say about the sex of the child, is it to be arranged that the numbers of boy babies and girl babies shall be kept roughly equal?

Russian research into geriatrics—that is, the nature of old age—is said to be starting to produce interesting results.

Even if there is no breakthrough there, it is unlikely to be very long before some advance is made.

What will happen when the average expectation of vigorous life can be raised to 100 years or more?

I tried in a story called “Trouble with Lichen” to foresee some of the results we could expect.

I started with the idea that everyone would welcome longer life as a wonderful gift, but the more I thought about it, the more doubtful I became.

I tried to imagine the feelings of a man expecting to reach the top of his business around fifty and retire at sixty-five.

Then he discovers that he must wait for his promotion until he is eighty, and go on to ninety-five before he retires.

It did not seem to me that he would be entirely happy about it.

Think, too, of a whole younger generation faced with unemployment because all the jobs are held, and held on to, by men and women who will be only middle-aged at eighty or so.

Nevertheless, one day, perhaps not so far away, the chance to live a longer life will be there, and some will want to accept it.

CHANGES

THAT is going to be one of the changes that really will alter our lives, right down to family level.

The differences in age between the youngest and the eldest child in a family will be much greater.

When discoveries of such importance are made it is not a question of whether we like them, or whether we put them to use or not, any more than it was with nuclear fission.

Once a discovery exists you can’t abolish it, or wish it out of existence.

Nor can you do anything to prevent it being made, for it may be made unintentionally, as the discovery of rayon was; or it may come from an unexpected direction, as DDT came out of the dyestuffs industry.

Once it is made, you are stuck with it. You may suppress it for a time, but the only use you can make of that time is to decide how best to handle it.

Once it is here, you have to learn how to live with it.

The direction of our own destiny will soon be in a new stage, but it is not an entirely new trend.

It began when we discovered that diseases were not just acts of God, and that it was possible to keep alive many a child that unassisted nature would have slain young.

The control of heredity will mean the checking of hereditary diseases such as haemophilia, the disappearance of inherited malformations, the elimination of colour-blindness and some types of asthma, and so on—benefits which no one would contest.

Also, there are mental qualities which are every bit as undesirable as physical defects.

Surely it would be a crime to allow a baby to inherit instability or criminal tendencies; and would it be fair to let it be just mediocre when it might be highly intelligent?

Once we have these powers we shall have to use them. Where they will lead us, and what kind of men and women they may cause our descendants to be even four generations hence, no one can foresee.

Homo sapiens has been having a longish pause: he has made virtually no progress for 20,000 years or so. Either he must go on, or fossilise.

Might it not be that control of heredity is the key he has been waiting for before he could go on?

The idea of change in ourselves is not welcome. Not many of us would object to become the ideal specimen of what we are, but our instinct is to resist the idea of a change that would take us beyond that.

In “The Chrysalids” and in “The Midwich Cuckoos” I used the idea that sooner or later homo superior is going to turn up, and the stories are mainly concerned with the kind of reception he is likely to get when he does.

It is a basically simple reaction. People will fear him because he has advantages over them, and they will try to suppress him. In both these tales I supposed that the superior kind would appear suddenly, as new types have often done in nature.

It made the issue quite clear—the new kind had to be got rid of before it became strong enough to defend itself.

If he comes through controlled heredity, however, there is no enemy. There is just ourselves—ourselves with little deficiencies remedied, little improvements made here and there, and then one or two more improvements added.

We are healthier, stronger, more intelligent, longer lived; perhaps we have keener powers of perception so that we have begun to think a little differently, perhaps that has improved our brains so that our heads have to be a little bigger to hold them

comfortably, and then just a little bigger still.

And then, presently, who are we? Are we still ourselves or have we become a different sort of mankind? Who can tell—and where is anyone to say “Stop!”?

We must not forget the factors of chance and accident. In a story called “Consider Her Ways” I supposed an experimentally cultured disease that got away and wiped out men 100 per cent., but women only 20 per cent.

Women were thus left to manage the world their own way, and proceeded to do so.

This curious state of affairs was imagined for entertainment and satire, but however highly improbable it may be, it is not impossible.

Moreover, if such a thing should come about, we could, even with our present skills, keep the race going by artificial insemination, so that it would, in time, recover.

The idea of its continuation as an entirely female world is a bit more fancy—and yet, I wonder.

If the kind of massed brainpower that was turned on to the production of the nuclear bomb were to be set to finding a means of parthenogenesis—that is, the ability to produce offspring without male assistance—I think I’d bet on success.

So far, you will have noticed I have been assuming that The Bomb will be kept safely behind bars.

If it is not, those of us who are left are not so likely to be concerned with improving our own heredity as with stopping the modifications of it from running wild.

FREAKS

IN “The Chrysalids” I imagined what the world might be like long after an atomic war.

The centres of radioactivity were still unapproachable, but round them were belts of country where the radiation, while not deadly, was strong enough to affect the genes of inheritance in animals and plants.

Little that lived there bred true to type.

The chief concern of the surviving communities of normal mankind then became to keep the freaks at bay, and rid themselves of any variations from what they considered to be the true human form.

They could not succeed, of course, any more than the present world population could succeed in keeping its various races distinct and pure.

Little by little, changes would creep in.

So there could, in a short time from now, exist two factors capable of stirring our evolution out of its 20,000 year pause in its progress.

One, violent and unpredictable, is here already.

The other, gradual, but unable to see more than a step or two ahead, is yet to come.

Nature is a much misused and sentimentalised word. Man is a product of nature. Therefore the ability to do all the things he does must lie in his nature, or he could not do them.

Consequently, all the things he does do are works of nature for which he has merely been the means.

Thus his discovery of agents which affect heredity could be the natural means of shaking him out of his pause, and setting his evolution on the move again.

FEAR

FOR my part, I do not think the active agent will be The Bomb—we fear it too much to use it on the scale necessary for it to be effective.

There seems more probability that it will remain in the background as a stabilising factor—and be very valuable there.

The invisible presence of an Omnipotence powerful enough to curb selfish ambitions is not—as the Children of Israel used to need reminding—necessarily a bad thing.

But if we take the other way, and set out to steer our own destiny, where are we going to find the knowledge we shall need?

How are we to know which is the road to disaster, and which is the true line we should take?

THE ANSWER, IT NOW APPEARS, LIES IN SPACE.

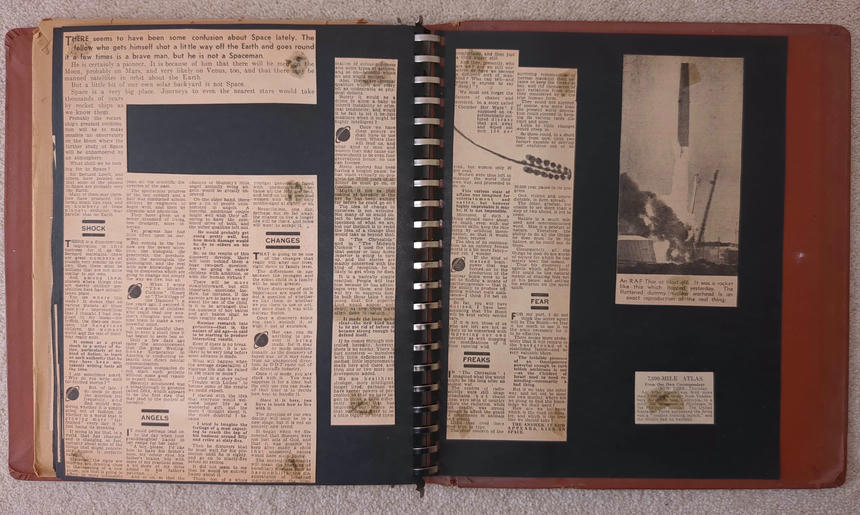

An RAF Thor at blast-off. It was a rocket like this which flopped yesterday. The flattened dummy nuclear warhead is an exact reproduction of the real thing.

7,000-MILE ATLAS

From Our Own Correspondent

NEW YORK, Thursday,

An Atlas missile was fired more than 7,000 miles to-day from Vandenberg Air force base, California, to a point 200 miles east of Mindanao, in the Philippine Islands. The United States Air Force announced the firing was a “routine training launch,” and the missile had no warhead.