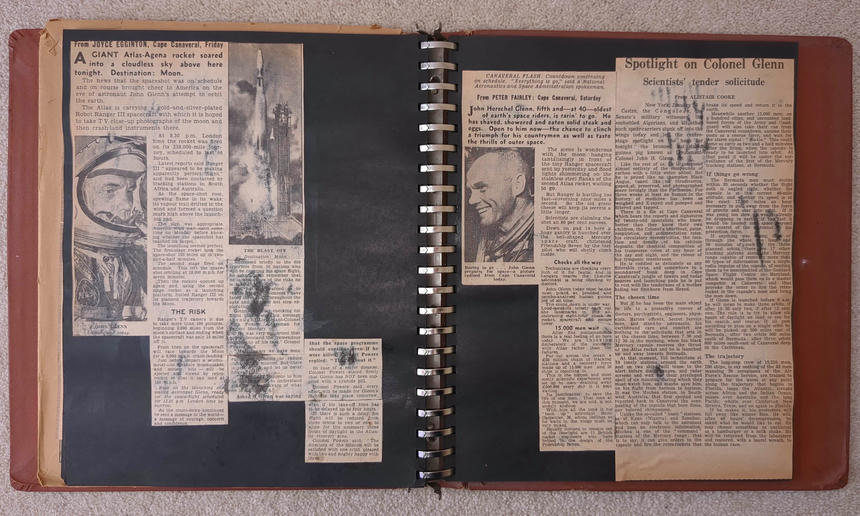

Scrapbook 1: Jan 1962 — Ranger 3, John Glenn

From JOYCE EGGINTON, Cape Canaveral, Friday

A GIANT Atlas-Agena rocket soared into a cloudless sky above here tonight. Destination: Moon.

The news that the spaceshot was on schedule and on course brought cheer to America on the eve of astronaut John Glenn’s attempt to orbit the earth.

The Atlas is carrying a gold-and-silver-plated Robot Ranger III spacecraft with which it is hoped to take TV close-up photographs of the moon and then crash-land instruments there.

At 8.30 p.m. London time the rocket was fired on its 238,000-mile journey, scheduled to last 66 hours.

Latest reports said Ranger III “appeared to be making apparently perfect fight,” and had been contacted by tracking stations in South Africa and Australia.

As the space-shot rose, spewing flame in its wake, its vapour trail drifted in the wind and formed a question mark high above the launching pad.

The sign was appropriate. America must wait until sometime on Monday before knowing whether the spaceshot has reached its target.

The launching seemed perfect. The first-stage rocket took the space-shot 150 miles up in two-and-a-half minutes.

The second stage fired on schedule. This left the spaceshot orbiting at 18,000 m.p.h. for seven minutes.

Then the rockets opened up again and, using the second stage rocket as a launching platform, hurled Ranger III on its planned trajectory towards the Moon.

THE RISK

Ranger’s TV camera is due to take more than 100 pictures, beginning 2,000 miles from the moon’s surface and ending when the spacecraft was only 15 miles off it.

From then on the spacecraft will race towards the Moon for a 6,000 m.p.h. crash-landing

Just before impact a seismometer—to measure moonquakes and meteor hits—will be ejected and slowed by retrorocket so that it can land at 150 m.p.h.

Back on the launching site waited Astronaut Glenn, ready for the space-flight scheduled for 12.30 p.m London time tomorrow.

As the count-down continued he sent a message to the world—a message of courage, concern and confidence.

THE BLAST OFF

Destination: Moon

Addressed briefly to the 600 reporters from 16 nations who will be covering his space flight, he asked us to remember that he is well aware of the risks he is taking.

But he also warned us to realise that “pioneers have faced these risks throughout the ages and that did not stop exploration.”

Glenn, still busy checking his flight plans, sent his message through Lientenant-Colonel John Powers, spokesman for Project Mercury.

“He was very concerned that you understand the tremendous complexity of his task,” Colonel Powers said.

“He is aware we have done everything possible to reduce risks in the mission. But there is still a risk and let us never forget it.

“If anything happens to him he wants people to understand that he is well aware of what he is undertaking.”

Asked if Glenn was saying that the space programme should continue even if he were killed, Colonel Power replied: “That’s about it.”

In case of a major disaster, Colonel Powers stated firmly that Glenn has NOT been supplied with a cyanide pill.

Colonel Powers said every effort will be made for Glenn’s flight to take place tomorrow, even if his take-off time has to be delayed up to four hours.

If there is such a delay, his flight will be reduced from three orbits to two or one, to allow for the necessary three hours of daylight in the Atlantic recovery area.

Colonel Powers said: “The directors of the mission will be satisfied with one orbit, pleased with two and mighty happy with three.”

CANAVERAL FLASH: Countdown continuing on schedule. “Everything is go,” said a National Aeronautics and Space Administration spokesman.

From PETER FAIRLEY: Cape Canaveral, Saturday

John Herschel Glenn, fifth and—at 40—oldest of earth’s space riders, is rarin’ to go. He has shaved, showered and eaten solid steak and eggs. Open to him now—the chance to clinch a triumph for his countrymen as well as taste the thrills of outer space.

The scene is wonderous with the moon hanging tantalisingly in front of the tiny Ranger spacecraft sent up yesterday and flood lights shimmering on the stainless steel flanks of the second Atlas rocket waiting to go.

But Ranger is hurtling too fast—coverning nine miles a second. So the old green cheese will keep its secrets a little longer.

Scientists are claiming the shot an 80 per cent success.

Down on pad 14 here a huge gantry is hunched over the bell-shaped Mercury space craft, christened Friendship Seven by the test pllot who will shotly climb inside.

Checks all the way

Technicians are checking every inch of it for faults. And in hangars nearby the 12-stone astronaut is being checked by doctors.

John Glenn today must be the most poked at, prodded and psycho-analysed human guinea pig of all time.

The count down is under way. Loud-speakers tersely bark out the landmarks in this all-embracing eight-hour check on rocket, spacecraft and escape tower.

15,000 men wait

After five postponements there is a real feeling of go here today. We are thinking deliberately of the successes with Atlas rather than the failures.

Far out across the ocean a £25 million chain of tracking stations and a recovery force made up of 15,000 men and 26 ships is reporting in.

This is the biggest and most costly scientific experiment ever set up by man—draining away £500,000 every day it is kept waiting.

Its justification: to save the life of one man. That man at this moment, we are told, is not unduly anxious.

With him all the time is his “back up” astronaut Scott Carpenter, 36, whose feelings as he waits in the wings must be very mixed.

Equally content to remain out of the limelight are 12 British rocket engineers who have helped in the design of the Friendship Seven.

Raring to go . . . John Glenn prepares for space—a picture radioed from Cape Canaveral today.

Spotlight on Colonel Glenn

Scientists’ tender solicitude

From ALISTAIR COOKE

New York, January 26

Castro, the Congolese, the Senate’s military witnesses, the embattled Algerians, and all other such spear-carriers slunk off into the wings today and left the centre-stage spotlight on the hero for tonight: the bronzed out dazed guinea pig known as Lieutenant Colonel John H. Glenn.

Like the rest of us, he is composed almost entirely of the compounds of carbon with a little water added. But he is prized like no champion Black Angus, tuned like no Stradivarius, gaped at, preserved, and photographed more lovingly than the Parthenon. For three weeks at least no human in the history of medicine has been so weighed and X-rayed and pumped and filtered and tapped.

There is a file at Cape Canaveral which bears the reports and signatures of twenty-odd specialists who know, better than they know their own children, the Colonel’s heartbeat, pulse, respiration, and sedimentation rates, his circulatory eccentricities, the location and density of his calcium deposits, the chemical composition of his transverse colon at any hour of the day and night, and the colour of his tympanic membranes.

He is coddled as delicately as any filterable virus, and somewhere in a sound-proof bunk deep in Cape Canaveral’s jungle of towers and radar sources and launching pads he is put to rest with the tenderness of a mother hiding her first-born from Herod.

The chosen time

But if he has been the main object in life to a protective convoy of doctors, psychiatrists, engineers, physicists, Marine officers, Secret Service men, and stand-by astronauts, his earthbound care and comfort are nothing to the solicitude that sets in at the chosen time, between 7 30 and 12 30 in the morning, when his black Mercury capsule receives the thrust of the Atlas rocket and he is launched up and away towards Bermuda.

At that moment, 510 technicians at 16 lonely stations around the earth and on two ships will tense to the alert before dials, gauges, and radar screens and wait for their privileged spell of six minutes, during which they must watch him, and maybe save him, on his flight from horizon to horizon. It was the Muchea station, in South-west Australia, that first spotted and reported back to Canaveral the overheating of the capsule that bore Enos, our beloved chimpanzee.

Unlike the so-called “basic” stations, as at Kano (Nigeria) and Zanzibar, which can only talk to the astronaut and pass on electronic information, Muchea is one of the “command” stations of the Mercury range; that is to say, it can give orders to the capsule and fire the retro-rockets that brake its speed and return it to the earth.

Meanwhile another 15,000 men, on a hundred ships, and uncounted land-based forces of the Army and Coastguard will also take their cue from the Canaveral countdown, assume their posts as a rescue force, and wait for the alarm signal: “No-Go.” This could come as early as two and a half minutes after the firing, when the capsule is ready to be launched into orbit. At that point it will be under the surveillance of the first of the Mercury tracking stations, at Bermuda.

If things go wrong

The Bermuda men must decide within 30 seconds whether the flight path is angled right, whether the capsule is at the correct 40-mile altitude, and whether its speed is at the exact 17,500 miles an hour necessary to pull away from the force of gravity and soar into orbit. If it was going too slow, it would already be dropping to earth; if too fast it would be headed into space beyond the control of the astronaut or his protection force.

If anything was wrong, then or through the whole one hour and 36 minutes of each of the three planned orbits, there are 17 other tracking stations along the Mercury range capable of receiving more than 60 types of information from a single radio impulse of the capsule, of sending them to be unscrambled at the Goddard Space Flight Centre in Maryland, which would pass them on to a master computer at Canaveral and thus provoke the order to fire the retrorocket in the capsule’s nose and bring the man down.

If Glenn is launched before 9 a.m. he will mean to make three orbits, if after 10 30 only two, if after 12 only one. The rule is to try to allow six hours of daylight on land or sea for his search and rescue. If all goes according to plan on a single orbit he will be picked up 500 miles east of Bermuda; after two orbits 500 miles south of Bermuda; after three orbits 800 miles south-east of Canaveral deep in the Caribbean.

The trajectory

The long-stop crew of 15,510 men, 100 ships, to say nothing of the 63 men manning 36 aeroplanes of the Air Force’s Rescue Service, are trained to prepare for the worst at any point along the trajectory that begins in Florida, loops the Atlantic, streaks across Africa and the Indian Ocean, passes over Australia and the long Pacific, whirls over California, New Mexico, Texas, and on again to Florida.

If he makes it, his protectors will fall away like winter flies. He will, after 48 hours’ decompression, be asked what he would like to eat. He may choose something as unclinical as a hamburger or a milk shake. He will be returned from the laboratory and restored, with a laurel wreath, to the human race.