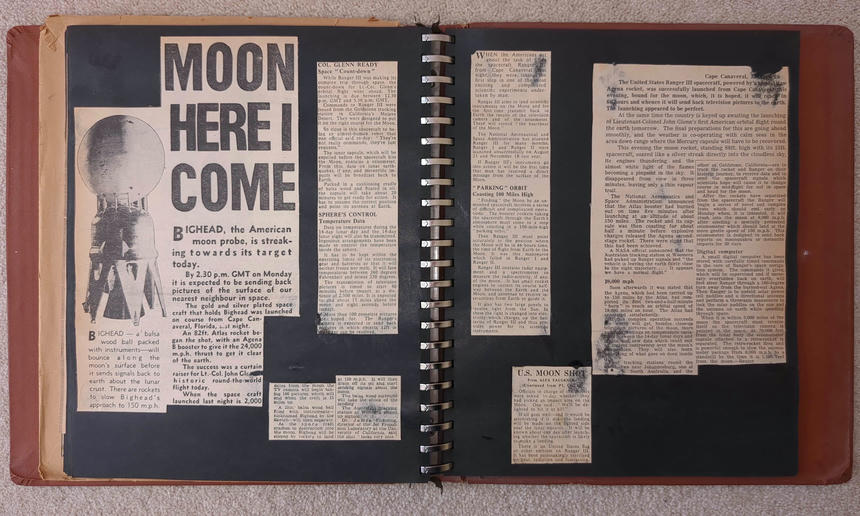

Scrapbook 1: Jan 1962 — Ranger 3

MOON HERE I COME

BIGHEAD, the American moon probe, is streaking towards its target today.

By 2.30 p.m. GMT on Monday it is expected to be sending back pictures of the surface of our nearest neighbour in space.

The gold and silver plated space craft that holds Bighead was launched on course from Cape Canaveral, Florida, alst night.

An 82ft. Atlas rocket began the shot, with an Agena B booster to give it the 24,000 m.p.h. thrust to get it clear of the earth.

The success was a curtain raiser for Lt.-Col. John Glenn’s historic round-the-world flight today.

When the space craft launched last night is 2,000 miles from the moon the TV camera will begin taking 100 pictures, which will end when the craft is 15 miles up.

A 25in. balsa wood ball filled with instruments—nicknamed Bighead by the Sketch—will then separate.

As the space craft crashes to destruction into the moon, Bighead will be slowed by rockets to land at 150 m.p.h. It will then drain off its oil and start sending signals about the moon.

The balsa wood surround will take the shock of the landing.

The Australian tracking station at Woomera picked up signals.

Dr. James Pickering, director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the University of California, said the shot “looks very nice.”

BIGHEAD—a balsa wood ball packed with instruments—will bounce along the moon’s surface before it sends signals back to earth about the lunar crust. There are rockets to slow Bighead’s approach to 150 m.p.h.

COL. GLENN READY

Space “Count-down”

While Ranger III was making its complex trip through space, the count-down for Lt.-Col. Glenn’s orbital flight went ahead. The launching is due between 12.30 p.m. GMT and 5.30 p.m. GMT.

Commands to Ranger III were issued from the Goldstone tracking station in California’s Mojave Desert. They were designed to put it on the right course for the Moon.

So close is this spacecraft to being an almost-human robot that one official said to-day: “They’re not really commands, they’re just requests.”

The lunar capsule, which will be expelled before the spacecraft hits the Moon, contains a seisometer. From this, data on lunar earthquakes, if any, and meteoritic impacts will be broadcast back to Earth.

Packed in a cushioning cradle of balsa wood and floated in oil, the capsule will take about 20 minutes to get ready for action. It has to assume the correct position and point its antenna at Earth.

SPHERE’S CONTROL

Temperature Data

Data on temperatures during the 14-day lunar day and the 14-day lunar night will also be transmitted. Ingenious arrangements have been made to control the temperature inside the sphere.

It has to be kept within the operating limits of its electronics gear and batteries so that it will neither freeze nor melt. It will face temperatures between 260 degrees Fahrenheit and minus 230 degrees.

The transmission of television pictures is timed to start 40 minutes before impact, at a distance of 2,500 miles. It is expected to end about 15 miles above the moon and eight seconds before impact.

More than 100 complete pictures are hoped for. The Ranger’s camera is expected to send back pictures in which objects 12ft in diameter can be resolved.

WHEN the Americans set about the task of firing the spacecraft Ranger III from Cape Canaveral last night, they were taking the first step in one of the most exciting and complicated scientific experiments undertaken by man.

Ranger III aims to land scientific instruments on the Moon and for the first time transmit back to Earth the results of the television camera and of the seisometer. These will record “the heartbeat of the Moon.”

The National Aeronautical and Space Administration has planned Ranger III for many months. Ranger I and Ranger II were launched unsuccessfully on August 23 and November 18 last year.

If Ranger III’s instruments go into action it will be the first time that man has received a direct message from the surface of the Moon.

“PARKING” ORBIT

Coasting 100 Miles High

“Finding” the Moon by an unmanned spacecraft involves a series of difficult and complicated operations. The booster rockets taking the spacecraft through the Earth’s atmosphere must come to a stop while coasting in a 100-mile-high “parking orbit.”

Then Ranger III must point accurately to the position where the Moon will be in 66 hours time, the time of flight from Earth to the Moon. It was this manoeuvre which failed in Ranger I and Ranger II.

Ranger III contains radar equipment and a spectrometer to measure the radio-activity, if any, of the moon. It has small rocket engines to correct its course halfway between the Earth and the Moon, and antennae to receive instructions from Earth to guide it.

It also has two large panels to receive light from the Sun. In these the light is changed into electricity which charges up the batteries of Ranger III and thus provides power for its scientific instruments.

Cape Canaveral, January 26

The United States Ranger III spacecraft, powered by a huge Atlas-Agena rocket, was successfully launched from Cape Canaveral this evening, bound for the moon, which, it is hoped, it will reach in 66 hours and whence it will send back television pictures to the earth. The launching appeared to be perfect.

At the same time the country is keyed up awaiting the launching of Lieutenant-Colonel John Glenn’s first American orbital flight round the earth tomorrow. The final preparations for this are going ahead smoothly, and the weather is co-operating with calm seas in the area down-range where the Mercury capsule will have to be recovered.

This evening the moon rocket, standing 88ft. high with its 15ft. spacecraft, soared like a silver streak directly into the cloudless sky, its engines thundering and the almost white light of the flames becoming a pinpoint in the sky. It disappeared from view in three minutes, leaving only a thin vapour trail.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration announced that the Atlas booster had burned out on time five minutes after launching at an altitude of about 150 miles. The rocket and its capsule was then coasting for about half a minute before explosive charges released the Agena second-stage rocket. There were signs that this had been achieved.

A NASA official announced that the Australian tracking station at Woomera had picked up Ranger signals and “the vehicle is leaving the earth fairly close to the right trajectory… . It appears we have a normal flight.”

18,000 mph

Soon afterwards it was stated that the Agena, which had been carried up to 150 miles by the Atlas, had completed its first two-and-a-half-minute “burn” to reach an orbital speed of 18,000 miles an hour. The Atlas had separated satisfactorily.

If this complex operation succeeds the world will get, besides close-up television pictures of the moon, more accurate readings on temperature variations between the 14-day lunar days and nights, and new data which could end an ancient controversy over the moon’s composition. They will also learn something of what goes on deep inside it.

Four tracking stations round the world—two near Johannesburg, one at Woomera, South Australia, and the other at Goldstone, California—are to track the rocket and Ranger on their historic journey, to receive data and to send the spacecraft signals which scientists hope will cause it to change course in mid-flight far out in space and head for the moon.

After the rockets have separated from the spacecraft the Ranger will begin a series of novel and complex feats which should end early on Monday when, it is intended, it will crash into the moon at 6,000 m.p.h. after ejecting a specially protected seismometer which should land at the more gentle speed of 150 m.p.h. This seismometer is designed to send back reports on moonquakes or meteorite impacts for 30 days.

Digital computer

A small digital computer has been stored with carefully timed commands in the core of Ranger’s space navigation system. The commands it gives, which will be supervised and if necessary overridden back on earth, will first steer Ranger through a 180-degree turn away from the burned-out Agena. Then Ranger is to unfold solar power cell paddles and a directional antenna and perform a three-axis manoeuvre to lock the solar paddles on the sun and the antenna on earth while speeding through space.

When it is within 5,000 miles of the moon the spacecraft must reverse itself so the television camera is pointed at the moon. At 70,000 feet from the lunar body the seismometer capsule attached to a retro-rocket is separated. The retro-rocket fires and is powerful enough to slow the seismometer package from 6,000 m.p.h. to a standstill by the time it is 1,100 feet from the moon.—Reuter

U.S. MOON SHOT

From ALEX FAULKNER (Continued from P1, Col […])

Officials in charge of the project were asked to-day whether they had picked an impact area on the Moon. One said: “We’ll be delighted to hit it at all!”

If all goes well—and it would be astonishing if it did—the landing will be made on the lighted side near the lunar equator. It will be known about one day after launching whether the spacecraft is likely make a landing.

There is no United States flag or other emblem on Ranger III. It has been painstakingly sterilised by heat, radiation and fumigation.